FIELD experience: Dr Kirsty Graham

Who are you?

I’m Kirsty Graham (they/she) and I’m a Research Fellow at the University of St Andrews. I’m currently working with Cat Hobaiter on her ERC funded project examining how great apes use gestures to communicate. I’m queer and let’s call it “left-wing”, and I feel like both my gender and political identities shape the work that I do and my experiences in academia. When I’m not working, I enjoy playing guitar, gardening (outdoors and indoors!), going for long walks, playing cooperative board games, cooking, and doing creative crafts. I’m also very involved in union and community organising.

I’m Kirsty Graham (they/she) and I’m a Research Fellow at the University of St Andrews. I’m currently working with Cat Hobaiter on her ERC funded project examining how great apes use gestures to communicate. I’m queer and let’s call it “left-wing”, and I feel like both my gender and political identities shape the work that I do and my experiences in academia. When I’m not working, I enjoy playing guitar, gardening (outdoors and indoors!), going for long walks, playing cooperative board games, cooking, and doing creative crafts. I’m also very involved in union and community organising.

What is your favorite field food?

I’m such a snacker, I always have snacks in my backpack and sometimes in my pockets! If you’re ever at a conference and start feeling hungry, come find me and I will feed you. Finding great places to eat is important to me at home and wherever I’m travelling. I lost a dangerous amount of weight in my first ‘field season’, largely because that was what other people told me should happen, which is tied up with particular masculinities around ‘doing field work’. It took some time for me to work through that, but I’ve always found a lot of pleasure in eating good food, so it’s been wonderful to reclaim that joy and eat those treats!

Tell us about your field work

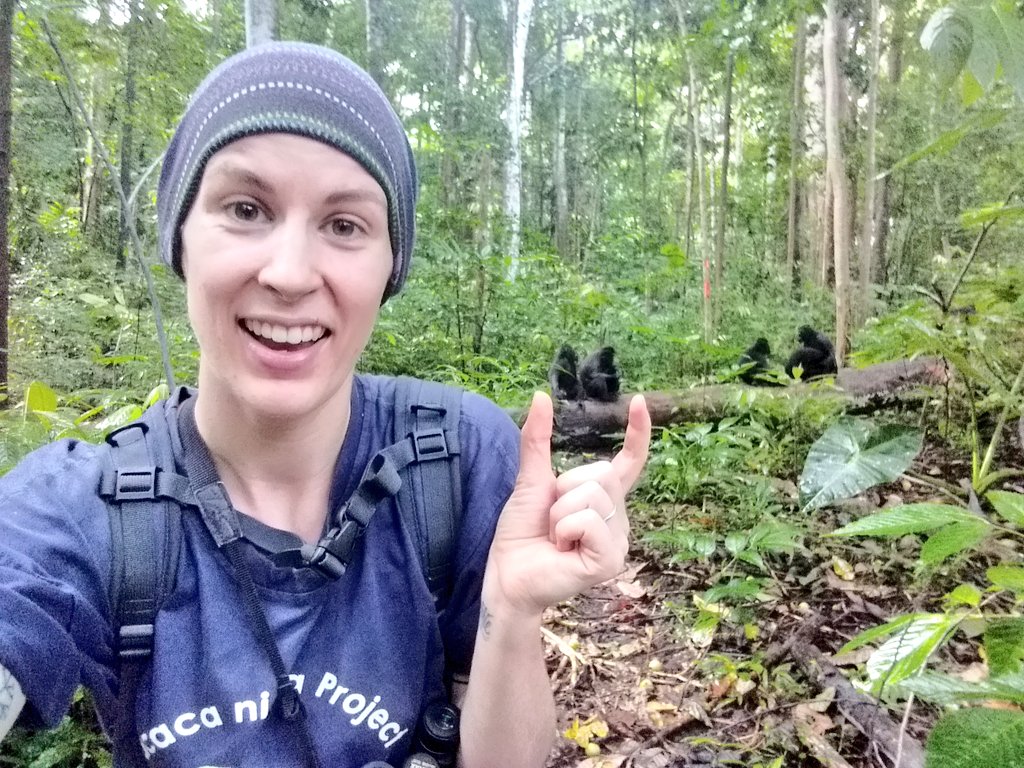

Most of my field work has been with bilia (bonobos) at Wamba in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, but I’ve also worked with a few species of monkeys in Costa Rica, chimps in Uganda, and yaki (Sulawesi crested macaques) in Indonesia. Nonhuman primates live in a specific geographical range that contributes to the exoticisation (and subsequent fetishization) of primatological field work. Problematising what we mean when we use the term “field work” is therefore especially important in our discipline, and I hope that these blog pieces can contribute to that discussion.

Most of my field work has been with bilia (bonobos) at Wamba in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, but I’ve also worked with a few species of monkeys in Costa Rica, chimps in Uganda, and yaki (Sulawesi crested macaques) in Indonesia. Nonhuman primates live in a specific geographical range that contributes to the exoticisation (and subsequent fetishization) of primatological field work. Problematising what we mean when we use the term “field work” is therefore especially important in our discipline, and I hope that these blog pieces can contribute to that discussion.

A lot of the things I love about field work are extensions of what I enjoy when not at work as well. I love spending time outside, wandering around the forest, watching other species do what they do. I also love trying to figure out why they are doing the things that they do, and what kinds of things they might be thinking and communicating about. Asking questions is a lot of fun!

Increasingly, as well as research, I find a lot of my motivation and energy coming through organising work, like the Animal Behaviour Collective. We’re a collective of researchers, from students through to lecturers, working together to provide microgrants and mentorship to students in animal behaviour who need it. I love working with folks who have similar values to imagine alternatives to current academic structures.

Increasingly, as well as research, I find a lot of my motivation and energy coming through organising work, like the Animal Behaviour Collective. We’re a collective of researchers, from students through to lecturers, working together to provide microgrants and mentorship to students in animal behaviour who need it. I love working with folks who have similar values to imagine alternatives to current academic structures.

Oh my days, the challenges! There’s the unpaid or underpaid labour, the insecure contracts (if you even have a contract), the deep structural inequalities, the harassment and bullying… honestly, it’s a lot. Financially, even if you have a funded PhD position, where are you getting the money for field work? For me, it took tight budgeting for groceries and not buying any “luxury” items, like new clothes (luxury, ha!), until I got a grant in my second year. It is no wonder that field work is such a site of privilege.

Oh my days, the challenges! There’s the unpaid or underpaid labour, the insecure contracts (if you even have a contract), the deep structural inequalities, the harassment and bullying… honestly, it’s a lot. Financially, even if you have a funded PhD position, where are you getting the money for field work? For me, it took tight budgeting for groceries and not buying any “luxury” items, like new clothes (luxury, ha!), until I got a grant in my second year. It is no wonder that field work is such a site of privilege.

The field site I was at in Indonesia was right on the beach, and swimming in the ocean after a day’s data collection is the most satisfying feeling! I had flippers and a snorkel and could spend my days off in the water. I grew up near the ocean and miss it when I live inland. That was a pretty challenging field season for me, and having the ocean right there (as well as living with close friends) was very important to my health.

The field site I was at in Indonesia was right on the beach, and swimming in the ocean after a day’s data collection is the most satisfying feeling! I had flippers and a snorkel and could spend my days off in the water. I grew up near the ocean and miss it when I live inland. That was a pretty challenging field season for me, and having the ocean right there (as well as living with close friends) was very important to my health.

How does your identity interact with your field work?

The UK, where I live, is growing increasingly hostile to trans and nonbinary people like me. Existing as a nonbinary person on the internet, I am constantly managing my profile – blocking accounts, muting words, limiting replies – to keep myself as safe as possible. Depending on where I travel to, it might be more or less dangerous to be openly queer, so I am constantly assessing that. But while I consider this when travelling to conduct field work, I don’t think this is unique to field work; coming out is something that LGBTQIA+ people are perpetually doing or not doing, making that decision in each new context we encounter.

(How) Is your identity recontextualized in this field setting? In other words, do you experience your identity differently at home vs in the field, and if so, how?

I have found that my queerness has been a non-issue in most of the places that I have conducted field work, because it is often shielded by my whiteness which, needless to say, affords me a number of privileges. I am frequently not expected to perform the gender of “woman” in the same way as local women racialised as Black or Brown, or at least my own gender representation is sometimes more acceptable as a white woman (or as a person who passes as a woman). Again, thinking about how we problematise field work is important here too, and my identity may be differentially recontextualised depending on the location and context of my field work.

What identity-based challenges have you faced in the field?

I did a bit of archival field work, digitising old videos, and during that period was sexually harassed by another PhD student. Sexual harassment is incredibly common in primatology (and I’m sure in field work more generally); many of the people reading this will have experienced, witnessed, or know about incidents of sexual harassment and assault. Through the “whisper network” we learn about many people in our field to avoid, which is a way of coping, warning, and claiming agency in a system that does little to challenge sexual violence.

How have you overcome these challenges?

I was in the lucky position of being line-managed by three women, all of whom were sensitive and supportive in assisting me to report the sexual harassment. I was happy with how the case was resolved; I’m an abolitionist and didn’t want him to be punished, I wanted him to never treat another person that way again. My case was relatively straightforward (as much as these things can be), but it can be extremely challenging to report sexual violence and I understand why many people don’t do it.

What advice might you have for someone preparing for a similar experience?

For avoidance of doubt: institutions and staff in positions of power have a duty of care to anyone who works with or for them. They should be the ones working to prevent sexual violence from continuing to occur in academia, and during field work specifically.

As an individual researcher, I recommend taking time to consider your own sexual health when travelling within and between countries. Do you have a supply of your preferred period products and contraceptives to last the duration, or have you identified where you can acquire them? Do you have condoms and emergency contraceptives, even if you are not planning to use them? Have you checked the relevant policies of the institutions you are affiliated with (e.g. relationship policy, gender-based violence policy)? Who is your emergency contact? How can you stay in touch with your support network at home?

How has your field experience influenced your perspective on diversity, equity, and inclusion?

I started doing field work in undergrad, and I was not really equipped to understand what field work is and how it functions. Imagine if all data collection that relied on the unpaid labour of international students and the low-paid and undervalued labour of local staff stopped tomorrow. Senior academics, field sites, and institutions are propped up by the exploitation of these students and staff members, which often reproduces familiar colonial and racialised inequities between global North and South. I used to be concerned only with the ethics of working with my study subjects, but I am now most concerned about the ethics of continuing to work within this system.

I’m Kirsty Graham (they/she) and I’m a Research Fellow at the University of St Andrews. I’m currently working with Cat Hobaiter on her ERC funded project examining how great apes use gestures to communicate. I’m queer and let’s call it “left-wing”, and I feel like both my gender and political identities shape the work that I do and my experiences in academia. When I’m not working, I enjoy playing guitar, gardening (outdoors and indoors!), going for long walks, playing cooperative board games, cooking, and doing creative crafts. I’m also very involved in union and community organising.

Most of my field work has been with bilia (bonobos) at Wamba in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, but I’ve also worked with a few species of monkeys in Costa Rica, chimps in Uganda, and yaki (Sulawesi crested macaques) in Indonesia. Nonhuman primates live in a specific geographical range that contributes to the exoticisation (and subsequent fetishization) of primatological field work. Problematising what we mean when we use the term “field work” is therefore especially important in our discipline, and I hope that these blog pieces can contribute to that discussion.

Increasingly, as well as research, I find a lot of my motivation and energy coming through organising work, like the Animal Behaviour Collective. We’re a collective of researchers, from students through to lecturers, working together to provide microgrants and mentorship to students in animal behaviour who need it. I love working with folks who have similar values to imagine alternatives to current academic structures.

Oh my days, the challenges! There’s the unpaid or underpaid labour, the insecure contracts (if you even have a contract), the deep structural inequalities, the harassment and bullying… honestly, it’s a lot. Financially, even if you have a funded PhD position, where are you getting the money for field work? For me, it took tight budgeting for groceries and not buying any “luxury” items, like new clothes (luxury, ha!), until I got a grant in my second year. It is no wonder that field work is such a site of privilege.

The field site I was at in Indonesia was right on the beach, and swimming in the ocean after a day’s data collection is the most satisfying feeling! I had flippers and a snorkel and could spend my days off in the water. I grew up near the ocean and miss it when I live inland. That was a pretty challenging field season for me, and having the ocean right there (as well as living with close friends) was very important to my health.